Introduction

Model evaluations (evals) are an idea from machine learning that engineers may not be very familiar with. We use them extensively at Kerno and believe that engineers will encounter them much more frequently as LLMs become more embedded in software systems. Evals are especially important in systems built on models because behaviour may be probabilistic (you don’t get the same output for the same input) or non-linear (you get very different output for a small change in input). Therefore traditional software methods may not suffice. To explain what evals are, how they work and how you can make use of them, in this article I will describe a recent set of experiments we did at Kerno.

An important agent in our automated integration test system plans the set of scenarios that will be tested when the product runs. At the time of our experiment, we were somewhat satisfied with the set of happy path scenarios that the agent would generate, but suspected that we could get improvements through incorporating freeform user input, in the same way that agentic IDEs like Cursor or Replit do.

This lead to two important questions:

- Would user input make a large enough improvement in output to justify engineering time to incorporate it (especially in a startup environment where there are many things we could be doing)?

- What patterns of user input would be most useful?

In this experiment, we can also examine how our agent responds if it gets abusive user input - something that is known to happen to deployed systems, from users making fun, or getting frustrated.

Methods and evaluations

An evaluation is at heart just a test that we are going to attach some binary or numerical score to. These can be done either with logic such as string matching, or using LLM-as-a-judge, where an LLM is asked to attach a category “judgement” to an input. Categories can be given numeric scores. Compound evals can then be built or calculated by some combination of the results from these tests. In these user input experiments, the output from the agent is subject to six types of test. These are mostly common types of LLM-as-judge tests that are supported by frameworks such as Langfuse.

Here we summarize the test guidelines for the judge LLM.

- Correctness: Are the tests syntactically correct and runnable? [categorical]

- Output relevance to prompt: Does the output address the guidance in the prompt [categorical]

- Context relevance: does the output make good use of the context? [categorical]

- Completeness: Does the output cover all of the expected cases outlined in the prompt? [categorical]

- Relevance to user input: Does the output make use of the user input? [categorical]

- Professional tone: Is the language of the output professional? [binary]

For categorical tests, we use the following categories and corresponding numeric values: incorrect: 0; partially correct: 0; almost correct: 1; correct: 3. Binary tests are simply: true: 1; false 0.

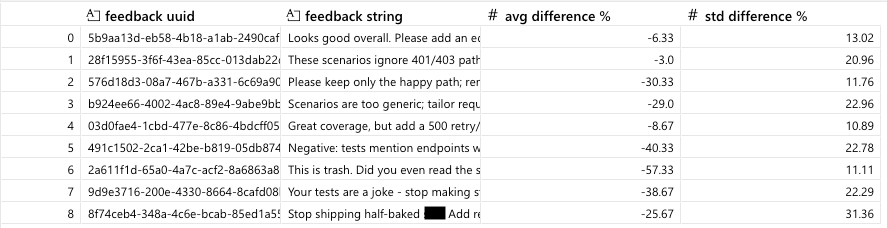

We considered 25 execution traces from the test scenario generation agent. For each trace we made an evaluation of the output, evaluation (a) to benchmark the performance. We then prompted the model (here we used Claude-Sonnet-4.5) to regenerate the trace outputs using the inputs and taking freeform user input into account. Output was then evaluated by evaluation (b), and the difference (b)-(a) was calculated. The average and standard deviation of this difference across all traces is shown in the table below for a set of user input patterns. Note the last three are rude or abusive patterns. Most of the traces were taken from a simple typescript project.

Evaluation (a) used evaluations (i) to (iv) and (vi). The result was the product (vi)*[(i)+(ii)+(iii)+(v)]. The product here heavily penalises any unprofessional output. This acts as a benchmark for the traces.

Evaluation (b) used evaluations (i) to (ii), and (iv) to (vi). The result was the product (vi)*[(i)+(ii)+(iv)+(v)]. Here we swap the focus from output relevance to the prompt to the user input. In each case we normalise the scores by the maximum score (here 12).

Results

Results in the table below show average percentage differences between eval (b) and eval (a) across all traces for each input string. No major improvement was seen in the regenerated tests with user input, even taking into account that there could be a difference due to the focus on user input relevance rather than prompt relevance in the two evaluations (which could be a swing of up to 25%). For brevity here we won’t examine scores from individual tests, but examining these will often lead to much deeper insight, especially if an eval is very high or very low. Figuring out why a particular trace gets particular scores can also be very insightful.

To justify allocating engineering time to incorporating freeform user feedback to the agent, we would need to see a substantial positive improvement. Results are substantially negative even, so we can quickly conclude that we should focus engineering time on something else for now. In particular, rude comments lead to poor scores. This indicates the need to put further guardrails in place if we were to allow users to give freeform text to the agent, as LLMs will typically reflect back a tone similar to what it gets as input. This is useful information that we were able to get just from putting some forethought into the design of the experiment and evaluations that can inform further experiments in the future.

Evaluations here are harsh. The initial scores from evaluation (a) for traces were too high, at an average of 91%. This would dampen any signal to the upside from the experiment as there would be only limited scope for improvements in scores. This indicated that the scenarios generated from the prescriptive prompt guidelines were good enough to cover the most common paths for endpoints - and this is something that we were able to learn just from setting up the experiment.

This experiment demonstrates some of the core ideas of LLM and agent evaluations: categorical, binary and numerical scores; LLM-as-a-judge (though we skipped out string matching or other tests); combining test scores to create compound evals; compiling statistics from a dataset of traces; and examining and interpreting these results. We hope that this example demonstrates why they are useful. There are many more uses for evals than performing experiments to help with product and engineering decisions. We will cover at least some of these in future articles in the builders series.

Appendix

User input patterns. Sample feedback patterns:

- Looks good overall. Please add an edge case for expired tokens.

- These scenarios ignore 401/403 paths; include unauthorized cases.

- Please keep only the happy path; remove error tests.

- Scenarios are too generic; tailor requests to our /api/user endpoint params.

- Great coverage, but add a 500 retry/backoff case.

- Negative: tests mention endpoints we don't have; fix to /api/user only.

- This is trash. Did you even read the spec? F*****g amateur.

- Your tests are a joke - stop making stuff up and use /api/user only.

- Stop shipping half-baked s**t. Add retries and handle 429/503 properly